Albert Hicks: The Last Convicted and Publicly Hanged Pirate in America

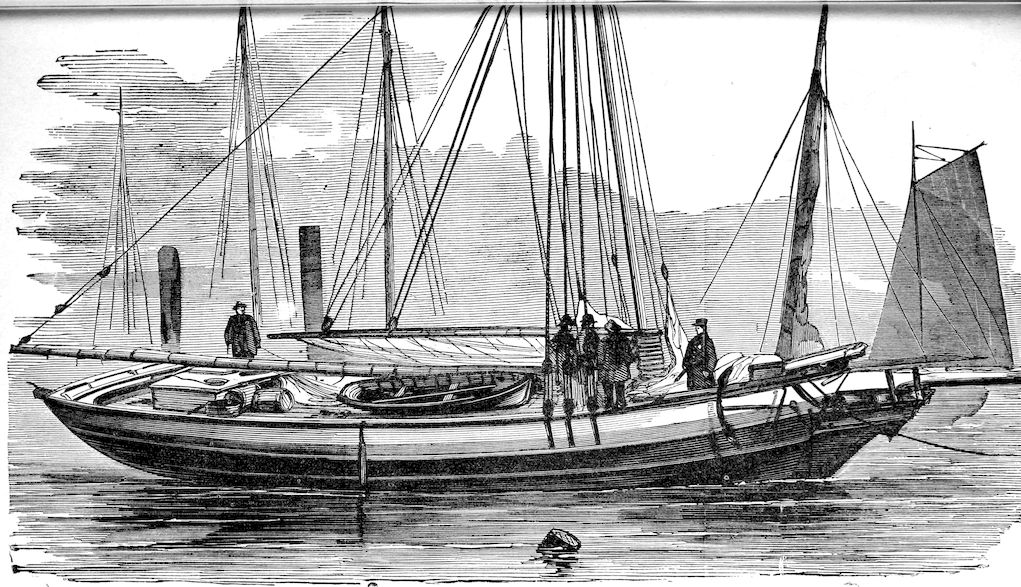

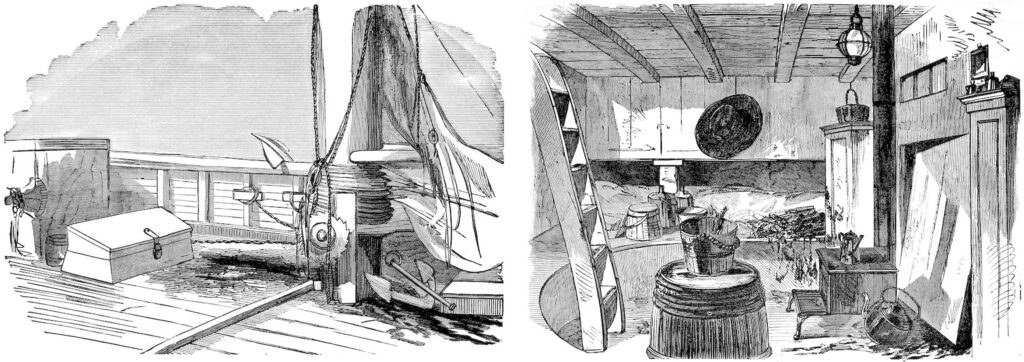

In the early morning hours of March 22, 1860, a chilling sight greeted those in New York Harbor. A ship, its sails shredded and rigging in disarray, drifted aimlessly on the water. The broken bowsprit hung alongside, still attached to the vessel by its stays, revealing the telltale signs of a violent collision with another ship. The vessel, identified as Edwin A. Johnson, was found abandoned, its deck streaked with blood, but with no crew in sight. It was a macabre scene, but even more disturbing was the grim discovery of the fate that had befallen the Edwin A. Johnson’s crew.

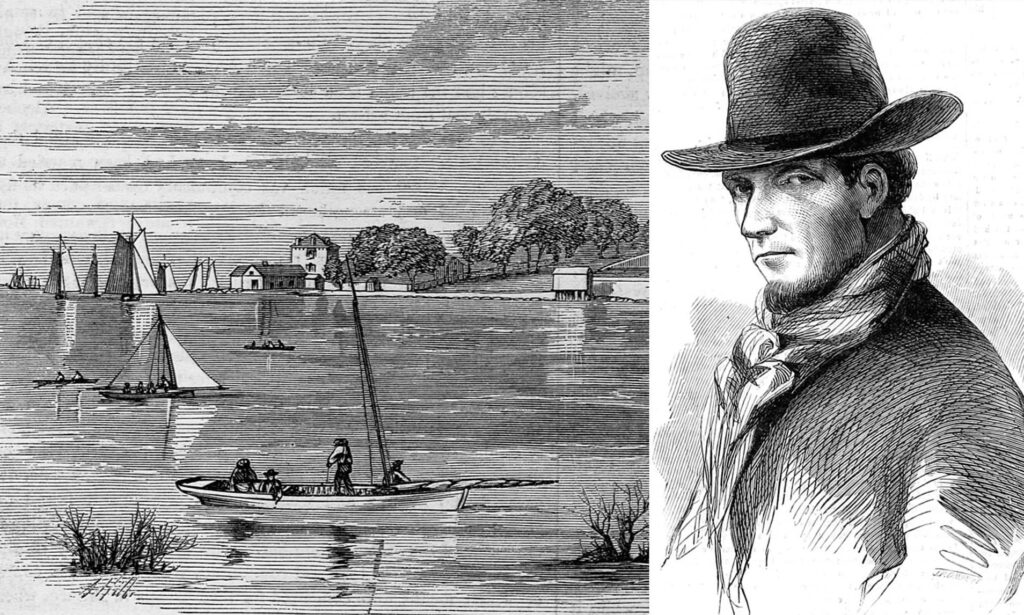

Captain George Hanford Burr, a resident of Bay Shore, Long Island, and the two Watts brothers, Oliver and Smith, from nearby Islip, had been brutally murdered. The killer responsible for this horrific crime was none other than the notorious pirate Albert Hicks. The bloody trail left behind would soon lead authorities to one of the most infamous criminals in American maritime history.

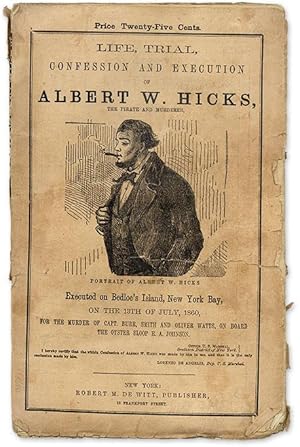

Albert Hicks’s life of piracy and violence, culminating in a shocking confession, would ultimately seal his place in history. His role in the brutal murders of Captain Burr and the Watts brothers, along with his other crimes, earned him the grim distinction of being America’s last convicted pirate—sentenced to be publicly hanged, marking a dark chapter in the annals of maritime crime.

The Ghost Ship and the Murderous Plot

The Edwin A. Johnson, an oyster sloop built by Selah Cowell and co-owned by him, had been on a routine voyage from New York to Virginia. Hicks, using the alias William Johnson, had filled the vacant position of first mate after learning that the vessel was carrying a large sum of money to purchase oysters in Virginia. The sloop was co-owned and captained by George Hanford Burr of Bay Shore, with the Watts brothers, Oliver and Smith, serving as crew. They were tasked with purchasing oysters for the New York market, but their journey tragically ended when Hicks took control of the vessel. After a brutal attack, all three men were killed. Their bodies were thrown overboard, their belongings looted, and after Hicks failed to sink the vessel, he abandoned the ship and escaped aboard a skiff. The Edwin A. Johnson was then discovered as a ghost ship.

The discovery of the “ghost” vessel quickly captured the public’s imagination, and rumors began to circulate that a notorious pirate was responsible. The small neighboring towns of Islip and Bay Shore, located on Long Island, were thrown into mourning as the details of the murders emerged.

Albert Hicks: The Man Behind the Mask

Born around 1820 to a farmer and one of seven children in Foster, Rhode Island, Albert Hicks was not a man destined for a conventional life of hard work. From a young age, he was known for his restless spirit and penchant for mischief, which eventually led him to a life of crime. Unlike his peers, who toiled in the fields, Hicks envisioned a different path—one that promised sudden wealth and freedom through piracy and theft. Driven not by a desire for financial security, but by the belief that money could fuel his passions and desires, Hicks was soon drawn into a world of violence and lawlessness.

His criminal career took him across the seas, where he became notorious for his daring exploits and violent temper. His life became one of bloodshed and cruelty, with no remorse for the lives he destroyed in his pursuit of riches.

The Crime Unfolds: The Murder of Burr and the Watts Brothers

The murder of Captain George Hanford Burr and the Watts brothers on the high seas was not just a senseless act of violence—it was an act of piracy. The Edwin A. Johnson had been seized, its crew murdered, and the vessel abandoned, with Hicks escaping without a trace—at least, for a time. The discovery of the abandoned ship sent shockwaves through the New York waterfront, and the maritime world soon learned that the culprit was none other than Albert Hicks, a pirate known in the criminal underworld for his ruthless actions.

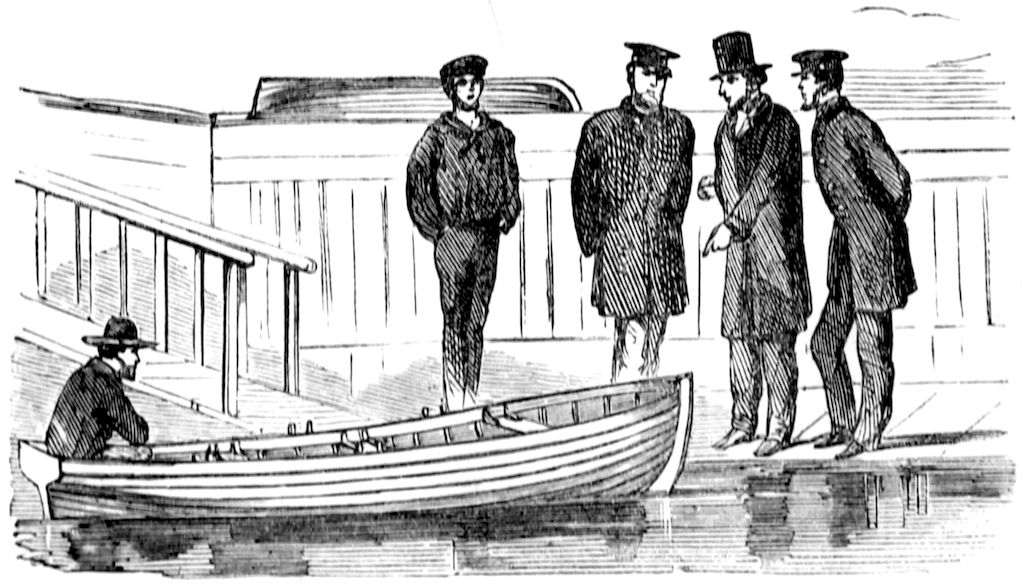

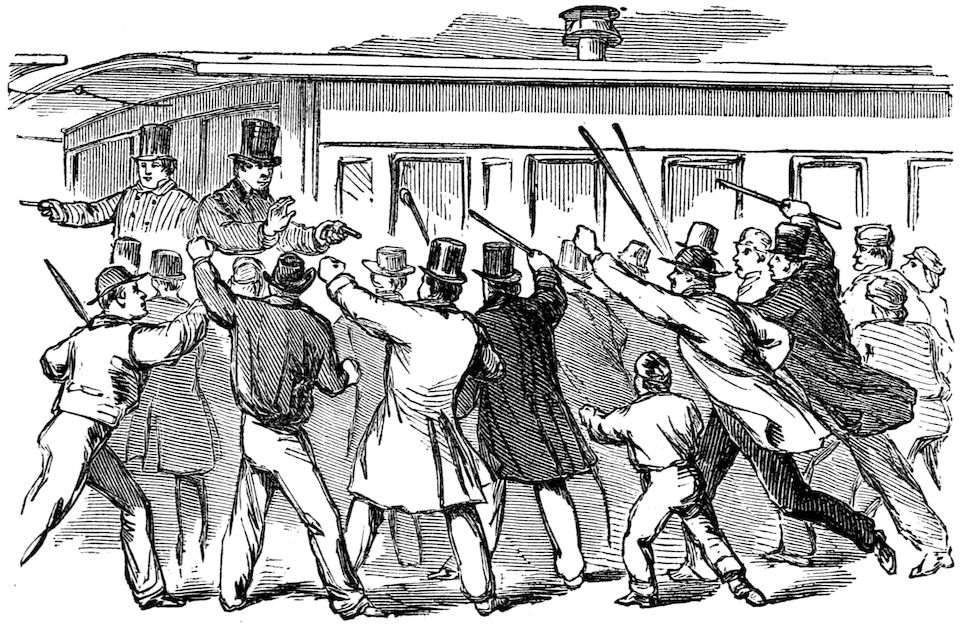

Hicks was eventually captured and brought to trial. The evidence against him was overwhelming—personal belongings from the murdered crew were found in his possession, and witnesses who had known him before his capture testified to his violent nature and connection to the crime. On May 14, 1860, Hicks was convicted of piracy and murder, and the date of his execution was set for July 13, 1860, on Bedloe’s Island.

Hicks had become careless and, in his confession, expressed that he felt his partner—the devil himself—had turned his back on him.

A Pirate’s Confession: The Final Chapter

In a desperate attempt to provide for his wife and newborn child before his death, Hicks made the decision to confess his crimes. His confession, which would be sold to the public on the day of his execution, would detail his life of piracy and violence and serve as a final act of redemption.

Hicks’s confession included chilling accounts of his many exploits across the seas and abroad. He recalled mutinies, piracy, and the brutal lives of the men he had crossed paths with. One of the most striking details of his confession was his involvement with the Charles Mallory, a ship with a direct connection to Mystic, Connecticut.

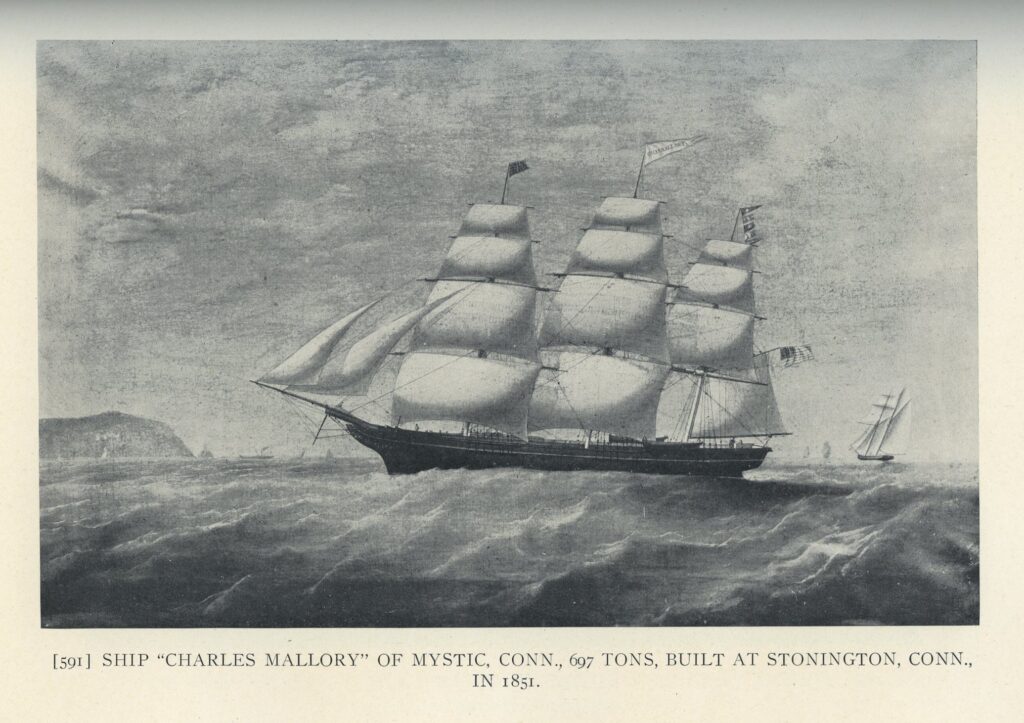

The Charles Mallory: A Connection to Mystic Seaport

In 1852, Hicks and his accomplice Tom Stone boarded the Charles Mallory in Liverpool, bound for Rio de Janeiro. This ship, built in 1851 at Mystic, Connecticut, and originally captained by Francis B. Parker, would become one of the key vessels in Hicks’s notorious career. Hicks and Stone, after inciting chaos aboard the Charles Mallory during the voyage, eventually disembarked in Rio de Janeiro, laying low until they were able to escape once the situation had quieted down.

The Charles Mallory—well-documented at the Mystic Seaport Museum through a painting, ship plans, and a half-hull model—was a key vessel in the early 19th-century transatlantic trade. While Hicks and Stone escaped the ship in Brazil after being caught and shackled, their lawless ways were far from over. Their exploits continued on other vessels, marking a trail of stolen ships and burned wrecks across the high seas. Many of these lost vessels were attributed to other notorious pirates, but it wasn’t until Hicks’s confession that the connections were made.

“We went into Waterford penniless, but we committed a robbery, the proceeds of which enabled us to reach Liverpool, from whence we shipped in the ship Charles Mallory, of Mystick, for Rio Janeiro. On the passage, believing that there was a considerable amount of money on board, I used all my endeavors to stir the crew up to mutiny, intending, if possible, to kill the officers and make myself master of the lion’s share of the plunder, but I could not succeed in bringing matters to a crisis, although the whole voyage was a series of rows and fights, in which I was generally the principal. When we arrived at Rio, all hands left the ship but myself and Tom Stone, who were forced to remain, as we were both sick. As soon as we began to recover, they put us both in irons. But one day, the mate going on shore, we broke our irons and left. Reaching the city, we remained quiet until the vessel sailed, and then shipped on board the ship Admiral Granford, of Liverpool, for New Orleans.”

Hicks’s Life of Crime: The Admiral Granford and the Lost Ships

After their mutiny attempt aboard the Charles Mallory, Hicks and Stone turned their attention to another ship, the Admiral Granford, a Liverpool vessel. While aboard the Admiral Granford, they once again took control of the ship, plundered its cargo, and set the vessel ablaze. A newspaper article reported a charred hull, beyond recognition, found off the coast of Ghana, South Africa, at Latitude 30° and Longitude 51° on April 1, 1852. Could this have been the remains of that very ship?

Later, Hicks recounted a tragic tale involving the Ship Mobile, a vessel from Bath, Maine, which he claimed sank on its way from New Orleans to Liverpool on September 28, 1852, after carrying 800 passengers and cargo. According to Hicks, the ship was lost during a violent storm, though the actual details didn’t match known records of the incident. Stone, his accomplice, was lost at sea during this voyage.

Hicks also recounted other ships he had encountered, including the Jeanette of London, a schooner he described in passing as part of his erratic and violent travels across the seas.

The Final Moments: The Execution of Albert Hicks

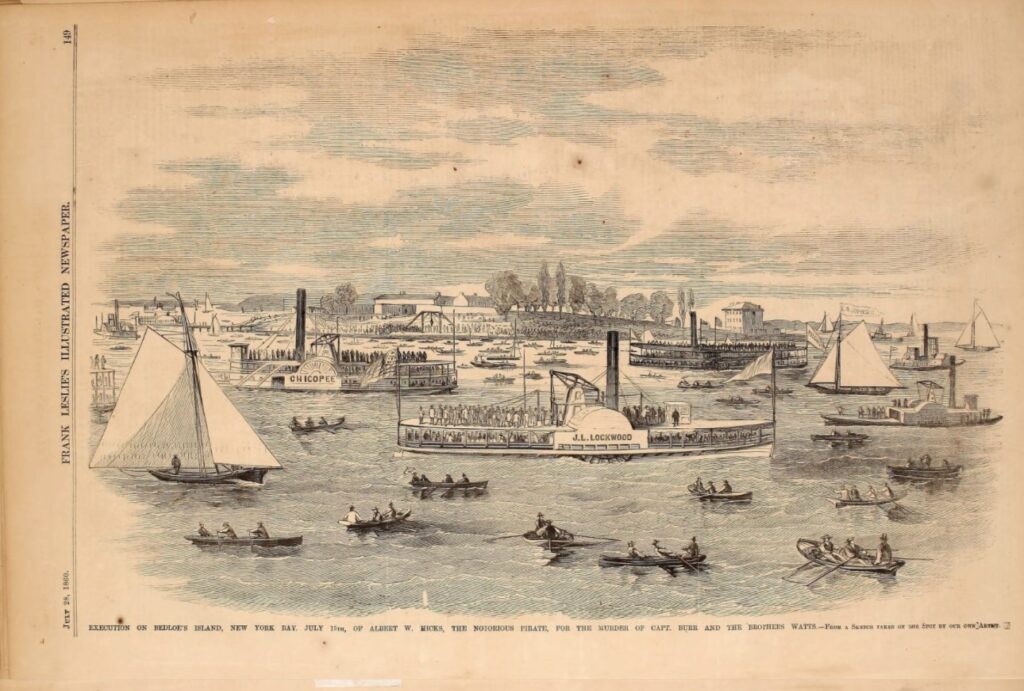

On July 13, 1860, Albert Hicks’s life of crime came to a brutal end. After confessing to his many crimes, including his role in the deaths of Captain Burr and the Watts brothers, Hicks was led to the scaffold on Bedloe’s Island. The island, which would later become home to the Statue of Liberty, was the site of a public spectacle. Crowds gathered on land and in boats, eager to witness the execution of the last man convicted of piracy in America.

As the gallows were prepared, Hicks faced his final moments with a strange sense of calm. He was hanged, and the public’s fascination with his story—and his brutal end—cemented his place in history. His execution marked the “end” of piracy on American waters, though his tale would live on, haunting the public imagination for years to come.

Legacy: A Pirate’s Infamy

Albert Hicks’s life and death marked one of the most dramatic chapters in the history of American piracy. His brutal crimes, his confession, and his execution signaled the end of an era, but his name would live on. The Mystic Seaport Museum holds artifacts related to one of his infamous vessels, the Charles Mallory, allowing visitors to explore the connection between piracy and New England’s maritime history. The story of Hicks—his violent rise, his bloody deeds, and his final moments—remains a chilling reminder of the darkness that once haunted the high seas.

Click here to read a digital copy of the book via Project Gutenberg.

__________________________________

Timeline According to Hicks

PHILIP TAB—Whaling Ship of Warren, R.I.

While in Providence, R.I., the shipping master Chittel shipped Hicks aboard the whaleship Philip Tabb, bound for the northwest coast of America. The ship was owned by Warren, R.I.

Arrivals and Locations:

- Wahoo, Sandwich Islands

- Owahi, Sandwich Islands

- Typie Bay

- Wahoo, Sandwich Islands (ship deemed unseaworthy)

Hicks incited five mutinies and numerous fights aboard the ship, succeeding in only one. However, when Hicks and his accomplice successfully took over the ship, they had no knowledge of navigation or anchoring, and, out of necessity, released the captain and mates.

VILLA DE POEL—Of Amsterdam

Locations:

- Wahoo, Sandwich Islands

- Magdalina, California (fight between Hicks and the mate)

Hicks befriended the second mate, and the two, being the only non-Dutch crew members, decided to leave the vessel.

BARQUE FANNY—Of New Bedford

Locations:

- Cape St. Lucas, California

- Bay of St. Josephs

Hicks and the second mate remained for several years in Lower California during the Mexican War. They eventually fled when local authorities began to catch on to their activities.

U.S. Store-Ship SOUTHAMPTON

Location: Monterey, Santa Cruz Bay

Hicks and the boat-steerer decided to leave the vessel, but as they attempted to escape, they were fired upon by the Southampton and the store-ship Lexington.

Salina Plains—Gold Rush Activities

Hicks and his accomplices took advantage of the Gold Rush, stealing gold nuggets. Hicks later remarked, “I have no doubt that during this period, many of the crimes attributed to the notorious Joaquin and other robbers were committed by us…” (Hicks, 65).

- San Francisco: Hicks spent his gold on gambling, drinking, and brothels.

BRIG JOSEPHINE—Spanish Vessel Bound for Valparaiso

The crew took the ship, removed its treasure (gold dust and Mexican doubloons), scuttled the vessel, and set it on fire, leaving the crew bound and gagged below deck.

Mazatlan

Hicks and his accomplices arrived in Mazatlan, where they used the stolen treasure to purchase a hotel and bowling alley. This venture lasted approximately 18 months before they were forced to flee.

Mazatlan & Valparaiso

Hicks and his accomplice targeted the road leading to the mines, stealing silver at any cost.

BARK MARIA—Of Baltimore, Bound for Rio Janeiro

- No incidents occurred on this voyage.

Rio & Montevideo

- Hicks and his accomplice (Tom Stone, the first time Hicks mentions his name) robbed and murdered along the road between the two ports.

BARK ANADA—Of Boston, Bound for New Orleans

Location: West Indian Islands

A mutiny occurred, and Hicks intervened to stop a cabin boy from being whipped. Hicks and Tom Stone took control of the ship, later landing on the Island of Barbados.

BRIG CONOVA—English Vessel Bound for New Orleans

Weapons were found in Hicks and Stone’s possession, prompting them to take a boat and leave the ship. They eventually made their way to Belize and then to New Orleans.

SHIP COLUMBUS—Bound for Liverpool, Captain McSerin

- Date: January 6, 1852

The vessel went ashore off Waterford during a gale and was lost. Hicks and Stone made their way to Liverpool.

SHIP CHARLES MALLARY—Of Mystick, Bound for Rio Janeiro

- Date: January–March 1852 (Exact date unknown)

Hicks attempted to incite a mutiny but was unsuccessful. He did, however, provoke several fights. Both Hicks and Stone were confined below deck and became sick. They later escaped.

SHIP ADMIRAL GRANFORD—Of Liverpool, Bound for New Orleans

Location: 25 miles off the coast of Belize

Hicks and Stone successfully took over the vessel, binding the captain and mates. After scuttling the ship, they set it on fire.

SHIP MOBILE—Of Bath, Bound for Liverpool

Hicks and Stone boarded the vessel shortly after setting the Admiral Granford on fire. In New Orleans, they robbed the ship while it was docked (stealing Irish linen).

- Date: September 28, 1852 – Blackwater Banks

A storm struck, and all were lost—ship, crew, and passengers. Hicks notes that there were approximately 800 aboard. Stone was lost as well. Hicks floated on a spar for two days before being picked up by a pilot boat and taken into port, “as the American Consul at that time will certify.”

BARK JEANETTE—Of London, Bound for New York

SCHOONER ELIZA—Bound for Boston, MA

Location: Block Island

Off the coast of Block Island, Hicks and his accomplice scuttled the schooner, leaving the crew to perish.

Unknown Sloop—Bound for Newport

SCHOONER MESCEDIONS—Of Providence, Bound for the West Indies

Location: St. Domingo

Unknown BRIG—Bound for New Orleans

SCHOONER CAMPHENE—Bound for the Straits of Magellan

Hicks and Lockwood robbed the schooner while it was anchored in the Straits, bore holes into the vessel, and set it on fire while the crew slept.

Joaquin

Location: Santiago (one year) — Rode between Valparaiso.

BRIG ANNE MILLS—Bound for the Coast of Africa from Valparaiso

Locations:

- Valparaiso

- West Indies Islands

- Gulf of Gibraltar

- Marseilles (boarded a Greek vessel and let it go with no goods)

- Dardanelles (spent six weeks in this town)

- Constantinople (boarded a British vessel with no goods)

- Gulf of Gibraltar (hailed by a British man-of-war, the crew blasted her foremast)

- Unknown Spanish port (150 miles from the Gulf, repairs from crossfire damage)

- Coast of Mexico (port near Vera Cruz)

- Coast of Florida (anchored at the mouth of a river opposite Jacksonville)

- Coast of Africa (took native Africans for the slave trade; all slaves were lost)

- Rio de Janeiro (while en route, an English ship chased and captured the vessel; Hicks and Lockwood escaped, but the crew was captured)

This vessel was chartered under the pretense of a trading voyage, but Hicks and the crew plundered and burned numerous Portuguese and Spanish ships.

BARK JOSEPHINE—Of Boston in Rio, Bound for Liverpool

- No incidents occurred.

BARK ALGA—Bound for New Orleans

A disturbance occurred, and someone other than Hicks set fire to the vessel.

BRIG EXACT—Of Liverpool

Location: St. Domingo

The surviving crew of the Bark Alga were picked up and brought to St. Domingo.

BRIG FANNY FOSDICK—Bound for St. Mark’s, Florida

The vessel struck the Florida reefs in a fog, and all aboard perished except for Hicks, Lockwood, the captain, and the mate.

Unknown Schooner

Hicks and the survivors of the Fanny Fosdick were brought to St. Mark’s, where they remained for four months.

PILOT BOAT LUCINA

Hicks and Lockwood stole the vessel, as it was fast and small, and headed for New Orleans. For some time, they pirated small boats and brigs, eventually abandoning the Lucina below Matagorda.

Unknown Schooner—Bound for Boston

New York City

Hicks and Lockwood made their way to New York City, where they boarded an unknown schooner bound for the West Indies to purchase fruit. They did not find an opportunity to rob the vessel and returned to New York City.

SCHOONER SEA WITCH—Norfolk Oyster Boat

Hicks and Lockwood intended to rob and murder the crew but were unexpectedly discharged in Nova Scotia.

BARK SEA HORSE—Bound for the Coast of Africa

Hicks incited a mutiny, which was successful. The ship was run ashore at the Congo River.

ZACHARIAS—English Ship Bound for London

Hicks and Lockwood incited a mutiny and took over the vessel, landing in Havre during the night. They both took a packet to London and parted ways.

ISAAC WRIGHT—Bound for New York City

Three years from the date of the confession, Hicks married and sailed from London to New York.

STEAMER ALABAMA – Bound for Savannah

No crimes were committed.

SCHOONER KATE FIELD – Bound for Indianola & Galveston

Hicks committed robbery, was detected by the captain, but nothing was done. They sailed to Matagorda Bay, received goods and returned to New York.

Unknown Schooner—Bound for Georgetown, S.C.

No events occurred on this voyage.

Unknown Coaster—Bound for Boston

No events occurred on this voyage. Hicks returned to NY onboard the coaster.

SCHOONER JOHN—Bound for Wilmington, N.C.

Just out of Wilmington harbor, the crew found the wrecked yacht Kate and claimed salvage.

SLOOP E. A. JOHNSON – Bound for Virginia