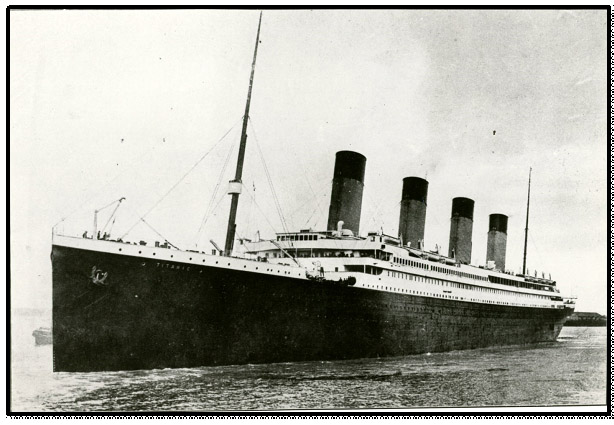

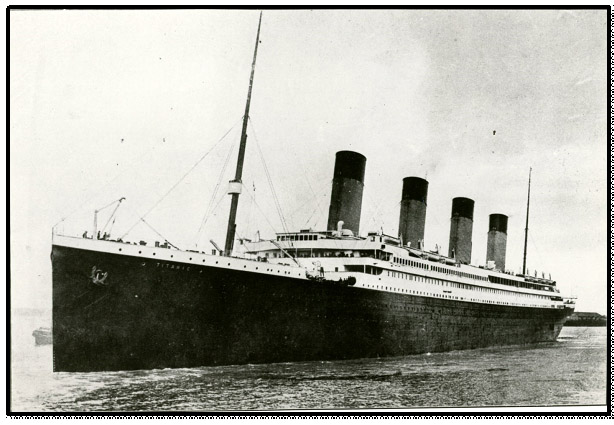

2020.39.7177 A photograph of the Titanic leaving Southampton, part of the Witherill Collection.

by Michelle Turner

The Titanic is so much a part of our collective memory and pop culture that the simple phrase “the band played on” may be enough to bring a lump to your throat. In the midst of a terrible disaster, on a cold and chaotic deck in the North Atlantic, the eight musicians of the ship’s band played ragtime songs and hymns, hoping to calm and soothe the people around them. Everything we know about those final moments comes to us from the memories of survivors. Many of them remembered being in their lifeboats and hearing music floating across the calm water as they rowed away. They remembered the music ending as the ship sank, replaced by the screams of people in the water.

A Carpathia discovery

We have been cataloging a collection of ocean liner materials donated by collector Linda Witherill, which includes many remarkable items directly connected to the Titanic and the disaster. But recently we discovered another small but chilling bit of the story hidden in a concert program.

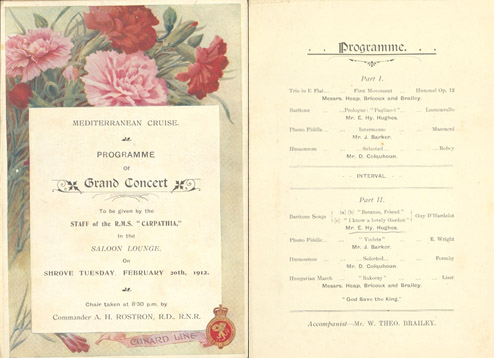

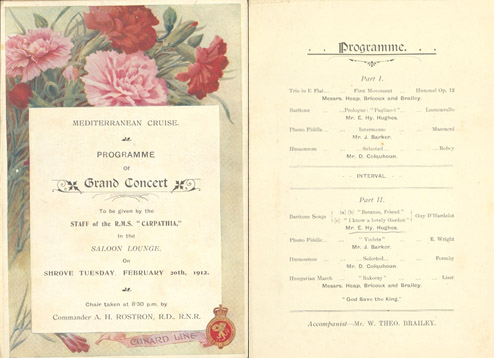

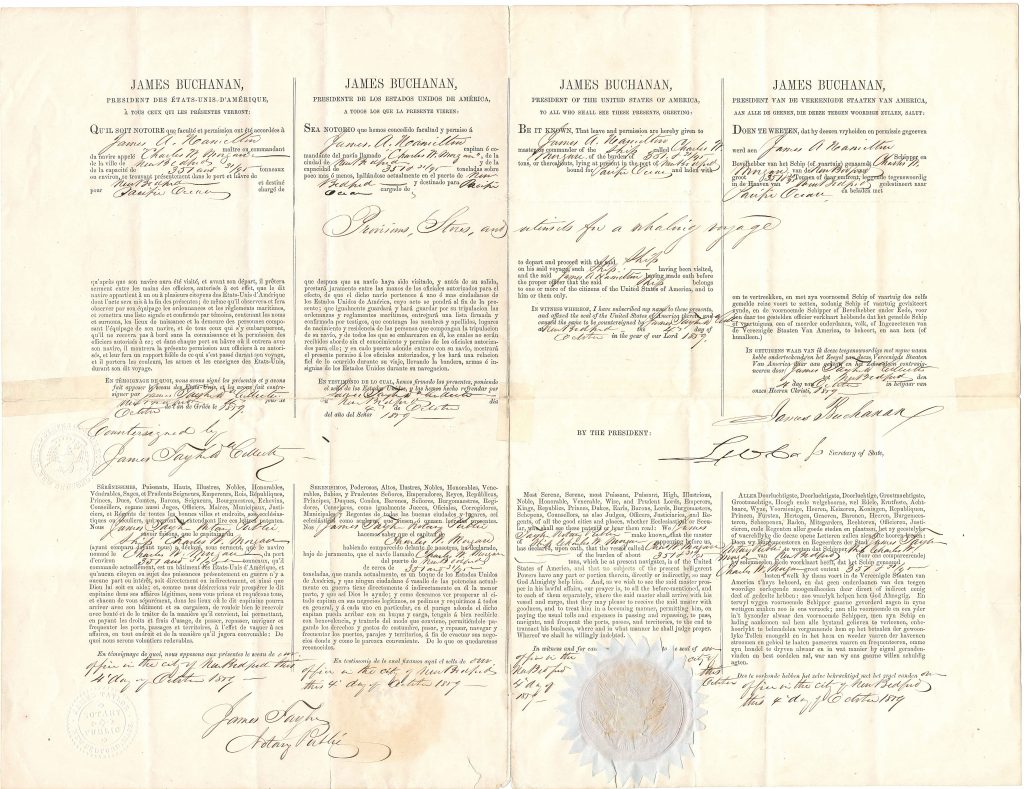

2020.39.7607 Programme of Grand Concert, from the Witherill Collection.

This is a program from a shipboard concert on the Carpathia, the ship that became famous for its heroic rescue of the 700 or so survivors of the Titanic after it sank on April 15, 1912. What you might notice first is the beautiful floral decoration. Then you might notice the date, February 20, 1912. And if you happen to know more about the Titanic’s story, you might notice the names of Roger Bricoux and William Theo Bailey. They were members of Carpathia’s band, but about a month and a half after this concert, they both signed up for the new band formed for the Titanic’s maiden voyage. (1) Like all of the Titanic’s musicians, they died in the disaster.

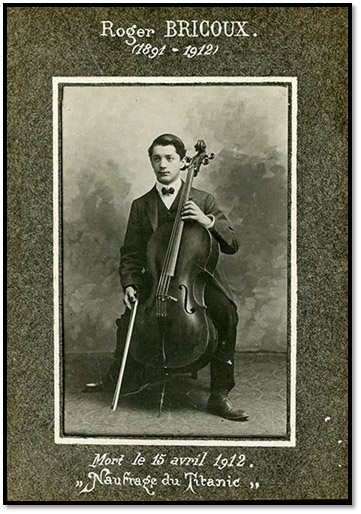

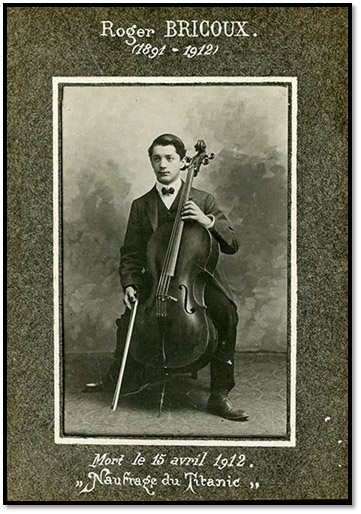

On this “Grand Concert” program, from the Carpathia’s February cruise from New York to the Mediterranean, the two of them are listed along with Edgar Heap, bandmaster and violinist. They played two classical pieces together. Theo Brailey, who also accompanied the other performers on piano, was 25 years old. Roger Bricoux, 23 years old, played the cello. Mystic Seaport Museum has recently acquired this incredible original photograph of Roger Bricoux.

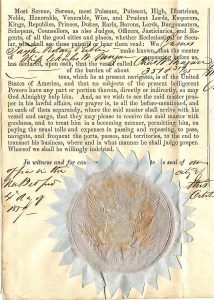

2022.51 Photograph of Roger Bricoux, a new acquisition

The Carpathia trip was Bricoux’s first time working as a musician at sea. On March 4, a few days after this concert, he mailed his parents a letter telling them about the trip: “The voyage is marvelous. We left Liverpool on February 10th and passed through Gibraltar, Tangier, Algeria, Malta, Alexandria, and Constantinople, then… Trieste, Fiume, Naples and finally New York. I assure you that it is splendid. We had a storm but I wasn’t at all sea sick. I was amazed.” On March 18, he wrote another letter telling them he would be joining the Titanic.

Back in New York on March 29, Bricoux and Brailey met with Wallace Hartley, the Titanic’s bandmaster, for the first time, and the three of them travelled back to England on the Mauretania. On April 10, the three boarded the Titanic, meeting up with the five other musicians, John Wesley Woodward, Jock Hume, John Clarke, Georges Krins and Percy Taylor.

Personal connections to the Titanic musicians.

The other performers listed on our Carpathia program were crew members. Because many of them were still on board the ship at the time of the famous rescue, we happen to know a lot about them. Captain Arthur Rostron was in attendance. Edward Henry Hughes, singing a baritone aria and songs, was the Chief Steward. Seventh Engineer Douglas Hamilton Colquhoun performed humorous songs. “Mr. J. Barker” may be James William Barker, an Assistant Storekeeper. (2)

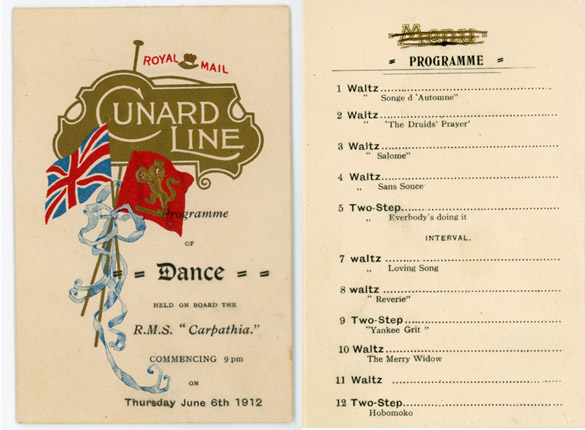

2020.39.7436 Postcard from Witherill Collection

2020.39.7445 Postcard from the Witherill Collection

On the night of the Titanic rescue, James Barker grabbed his camera. The pictures he took, reproduced on these postcards in the Witherill collection, represent almost the only photographic evidence from that terrible night.(3)

It is chilling to realize that crew members on the Carpathia had personal connections to people on the Titanic, had shared a stage with these two talented young musicians. When the Carpathia arrived on the scene at 4 am, after steaming at top speed, they expected to find a badly damaged ship, but all they found were 20 lifeboats in an icy sea. Not until the first survivors were brought aboard did they fully realize that the Titanic had sunk at 2:20 a.m.

What did the band play?

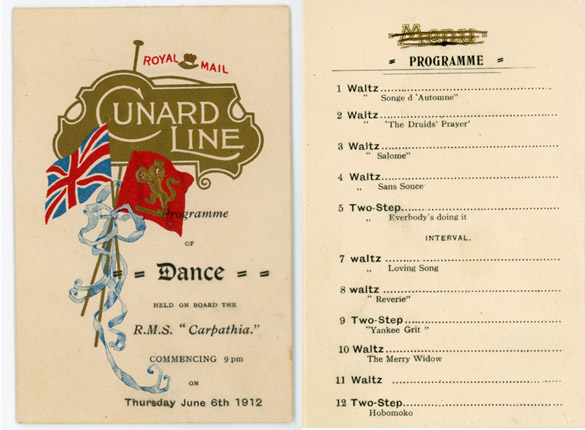

Our collection also gives us some hints about the music. This dance card from the Carpathia, from June 6, 1912, is an indication of what was popular at the time.

2020.39.7616 Programme of Dance, June 6, 1912, from the Witherill Collection

As for the Titanic, there is lively debate about what exactly the band played and especially about the last song they played. (4) Some survivors remembered dance music, and others clearly remembered them playing the hymn “Nearer My God to Thee.” Wallace Hartley, the bandmaster, had once told a friend that if he ever found himself on a sinking ship he would play “Nearer my God to Thee,” and that hymn became firmly associated with the disaster in the public’s mind, as these postcards from the time show.

2020.39.7262(left) and 2020.39.7265(right) Two of a set of Bamforth & Co. commemorative postcards in the Witherill Collection.

However, one survivor remembered that the last thing they played was a song he called “Autumn,” which might have been a hymn but might have been a reference to the beautiful waltz “Songe d’Automne.” Poignantly, that very waltz is the first selection on the Carpathia’s dance program.

We’ve created a Spotify playlist with a taste of the music from these objects and from the disaster.

TITANIC Playlist

For much more detail about the musicians and the music, we recommend the book “The Band That Played On: The Extraordinary Story of the 8 Musicians who Went Down with the TITANIC” by author Steve Turner

END NOTES

(1) The Carpathia was a Cunard Line ship, while the Titanic was a White Star Line ship. However, band members were not officially employees of the line. They worked for a company that contracted musicians to all of the steamers. Each line had standard books of music that musicians were expected to know and be able to play at the request of passengers.

(2) Barker was listed as playing a “phonofiddle.” This was an instrument that was briefly popular in the early 20th century, with a neck like a violin, but with a trumpet like a phonograph rather than a traditional violin body.

(3) At least two passengers took photographs as well, and there is some confusion as the photographs that these postcards attribute to Barker have sometimes been attributed to passenger Louis Mansfield Ogden.

(4) It is also unclear what instrument the pianist Brailey would have been playing, but author Steve Turner notes that he played multiple instruments, so perhaps he picked up something else to play that night.

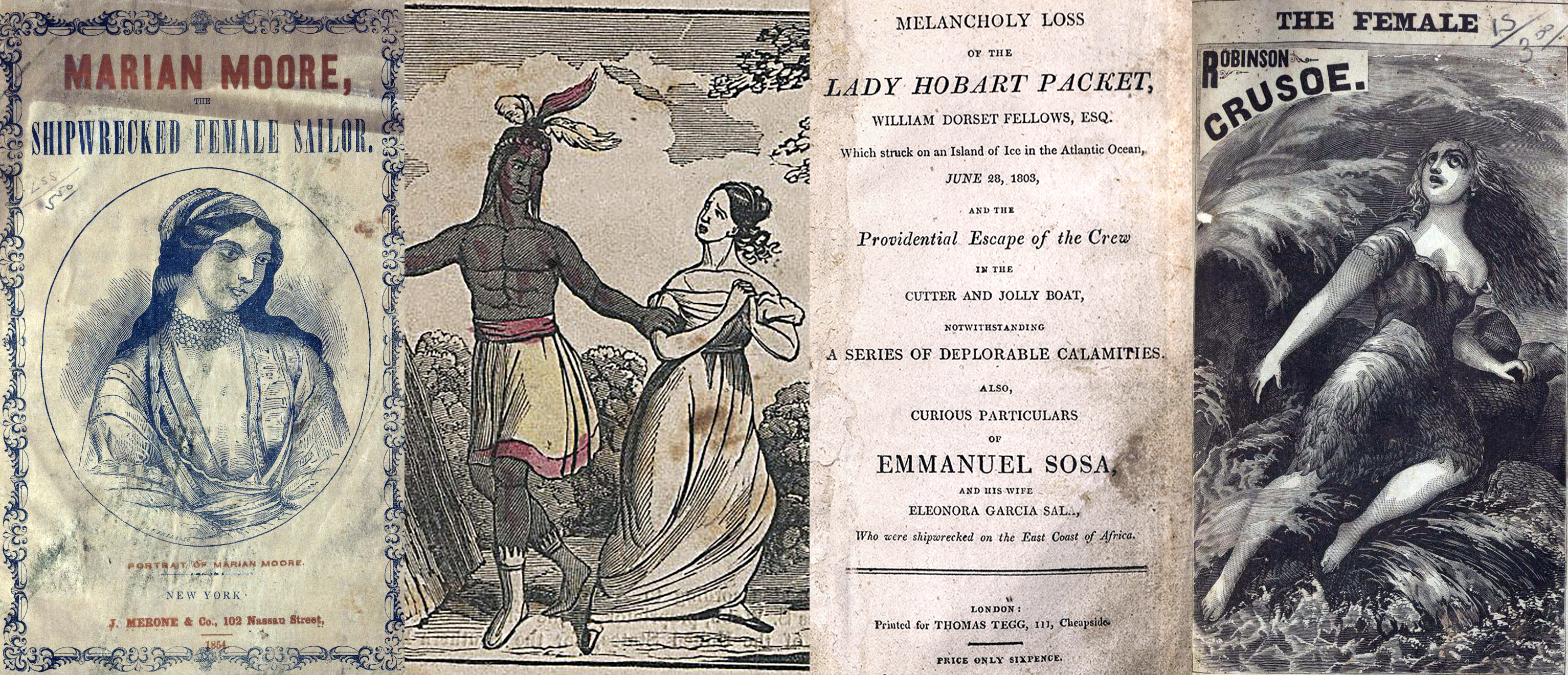

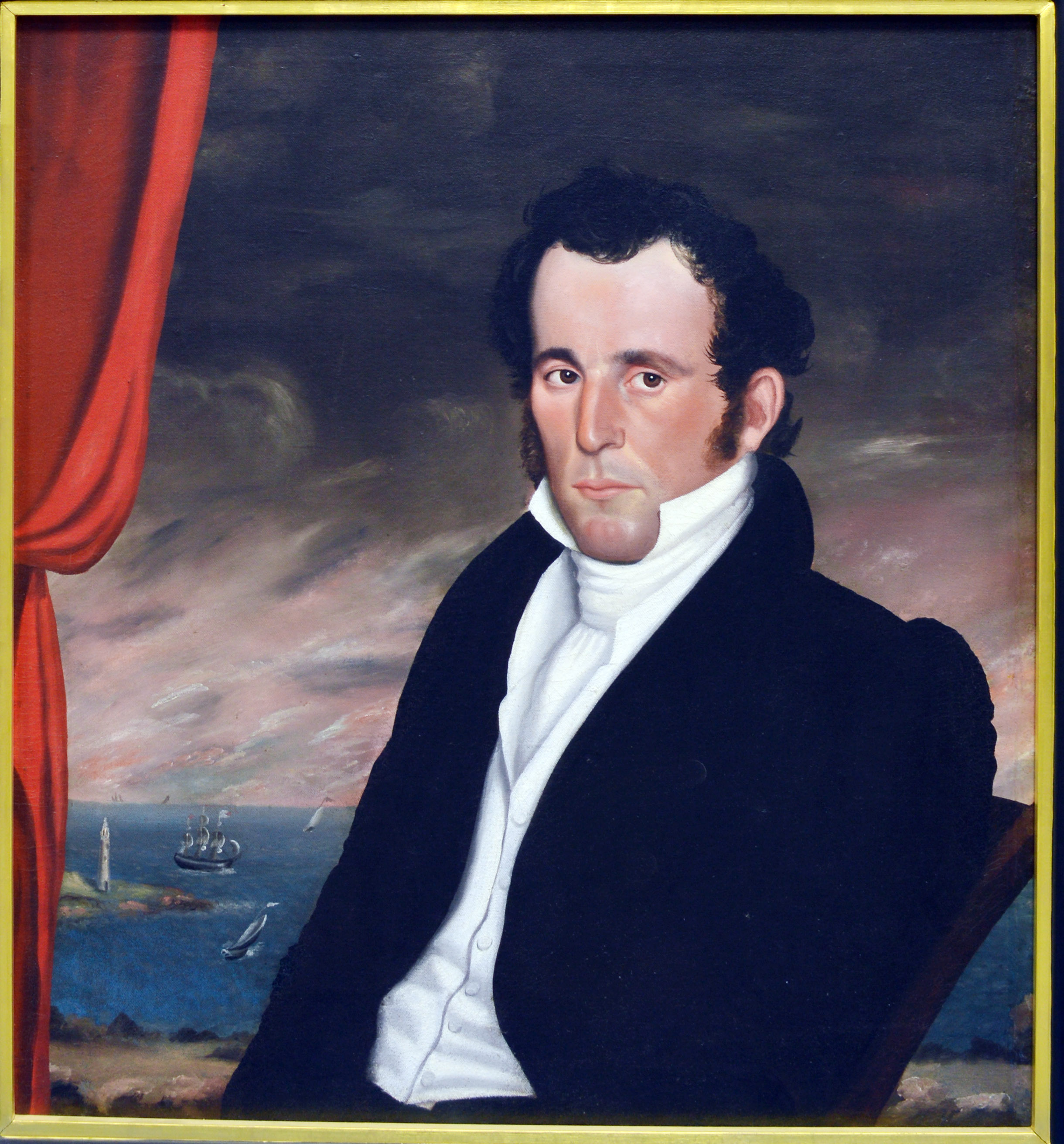

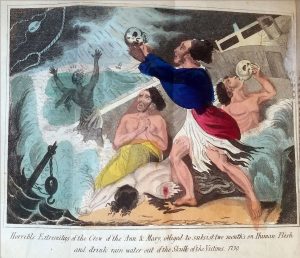

about 18 pages long and measures, in size, about 3 inches by 5 inches. But in it are three tales of shipwreck, the most gruesome of which is illustrated here. The book is so tender that we decided to photograph it immediately to

about 18 pages long and measures, in size, about 3 inches by 5 inches. But in it are three tales of shipwreck, the most gruesome of which is illustrated here. The book is so tender that we decided to photograph it immediately to