The Mystery of the Wanderer: A Vessel of Beauty, Deception, and Dark Legacy

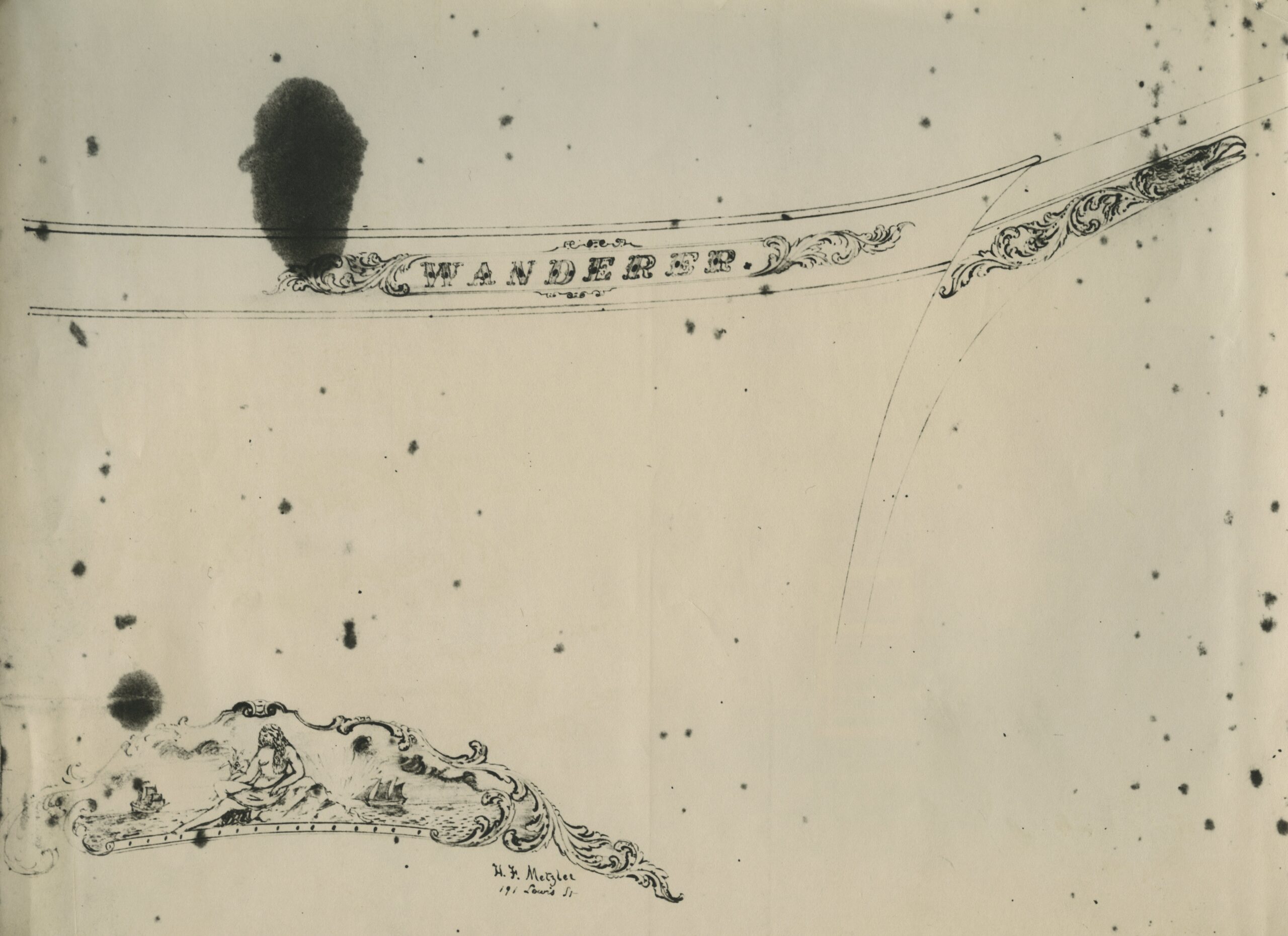

As I wandered through the vault of the Collection Research Center at the Mystic Seaport Museum, my eyes were drawn to a striking painting of a schooner-yacht, its sails billowing as it raced across the horizon. The image seemed alive, as though the very wind filling its sails was spilling out beyond the frame, whispering a forgotten story waiting to be told. The Wanderer is no mere ship—it is a vessel of innovation, prestige, beauty, betrayal, and war, carrying a legacy that claims all who are drawn to its dark past.

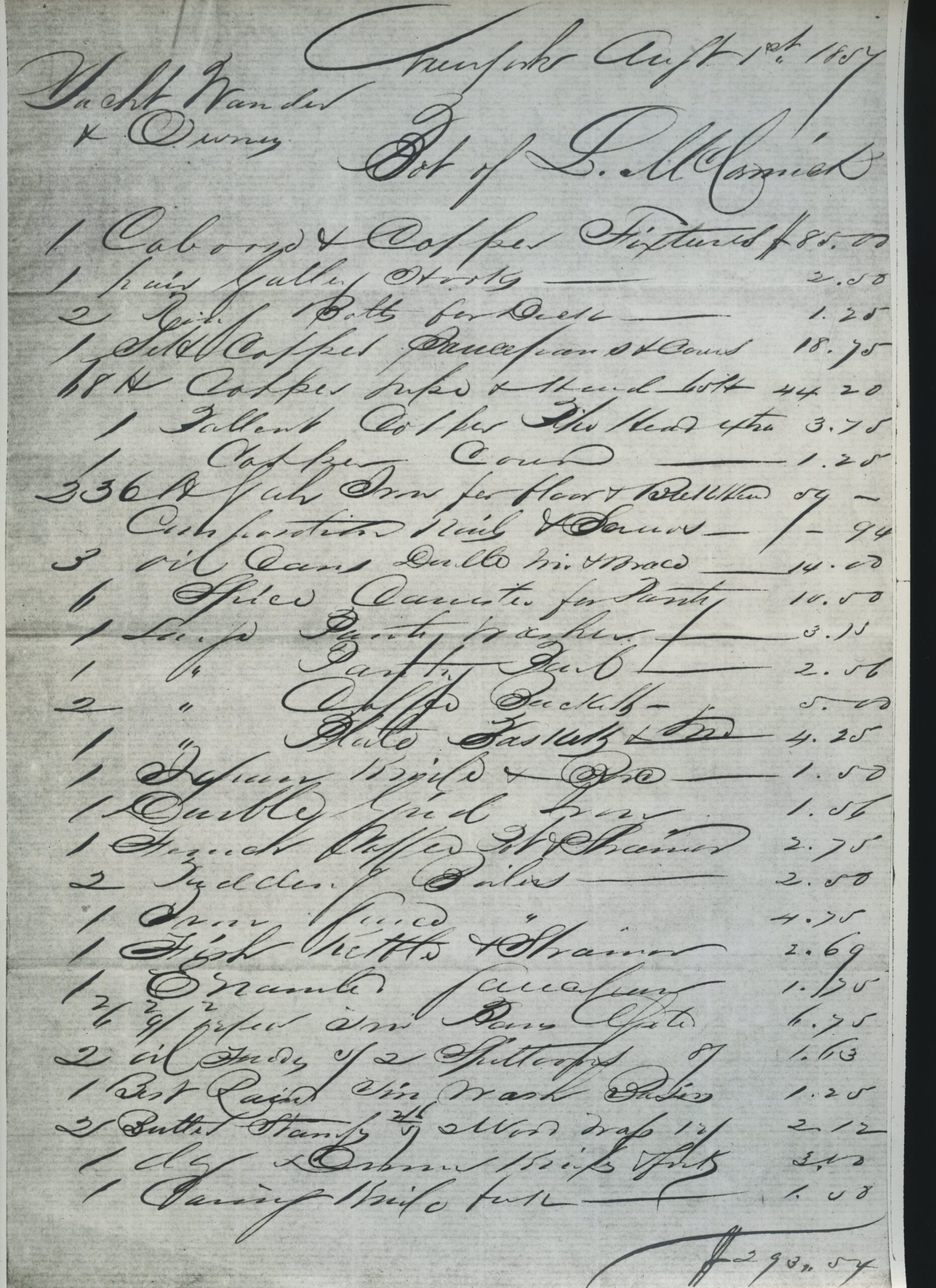

Nearby, a finely crafted chair caught my attention—its intricate carvings and luxurious materials silent yet evocative. This is the very seat Captain Thomas B. Hawkins likely occupied aboard The Wanderer, his jacket—perhaps the one he wore as its master—hanging nearby. One can almost imagine him in his blue wool tailcoat, New York Yacht Club gold buttons gleaming, seated on deck, gazing at the sea. Below, in the elegant galley, the scent of freshly prepared fish fills the air, served on a white plate inscribed with the yacht’s name. Proud and content, Hawkins admires the sunset, the yacht’s decks a symbol of his craft and dedication.

Launched on June 19, 1857, from W. J. Rowland’s shipyard in Port Jefferson, New York, The Wanderer quickly gained fame for its luxury and craftsmanship. Under Captain Hawkins—a respected mariner and boat builder born and based in Setauket, Long Island—the schooner-yacht became renowned for its sleek design and exquisite details. Commissioned and owned by Colonel John D. Johnson, it was celebrated as a marvel of shipbuilding—built for both speed and elegance. Its gleaming deck and lavish interiors symbolized Johnson’s wealth and taste, including a $1,400 upholstered chair, a stunning display of opulence.

As a “luxury racing yacht,” The Wanderer became a status symbol at the New York Yacht Club, admired for its beauty and speed. But its journey soon took a darker turn.

When Colonel Johnson sold the yacht to William Corrie, a smooth-talking Southern gentleman and a recent New York Yacht Club member, The Wanderer was unexpectedly repurposed for an illegal mission: the slave trade. Behind Corrie was Charles A. L. Lamar, a radical Southern secessionist who secretly purchased the yacht and orchestrated the operation. Lamar sought to bypass the 1808 U.S. ban on the international slave trade, using Corrie as a front to carry out his plan.

In 1858, The Wanderer set sail under the flag of the New York Yacht Club, cloaking its dark mission in respectability. Its goal was to sail to Africa, procure enslaved people, and bring them to the South. On November 28, 1858, the yacht successfully landed around 407 enslaved Africans on Jekyll Island, Georgia. This illegal voyage marked one of the last known slave shipments to the U.S., provoking national outrage and reigniting abolitionist movements.

The Wanderer’s involvement in the slave trade exposed the deepening divide between North and South. In the North, where slavery had been abolished, the yacht’s mission was seen as a moral affront. In the South, it became an act of defiance against federal law—symbolizing resistance to abolition. The yacht became a focal point in the national debate over slavery and the looming Civil War.

Today, The Wanderer is largely forgotten, viewed as a curiosity rather than an object of admiration. Yet its story remains a powerful reminder of the complex ways in which wealth, ambition, and power have shaped American history. What began as a masterpiece of shipbuilding and a symbol of elite status became, through a series of fateful decisions, an emblem of one of the nation’s darkest chapters.