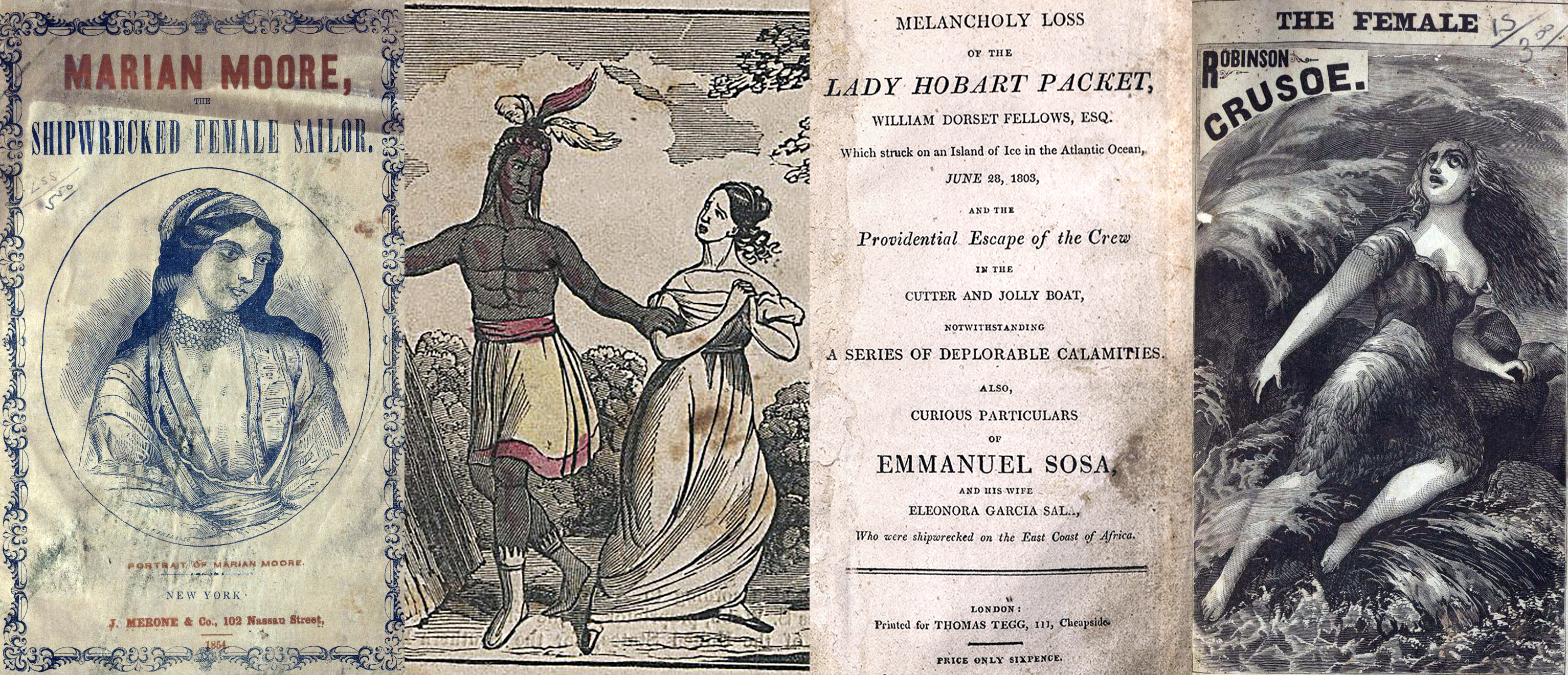

This project was sparked when I came across a description of Marian Moore’s personal narrative in the Mystic Seaport Collections Research Center online catalog. I wanted to know more about this “melancholy” woman who presented as a man at sea, and the harrowing details of her experiences with cannibalism and shipwreck, but there was no digital version of the text available at that time. Thus, a partnership began between the University of Rhode Island and the Library at Mystic Seaport Museum which allowed me to collaborate with the Museum in an effort to make several compelling narratives of shipwrecked women at sea available to scholars and enthusiasts around the globe through digital access.

Below are links to the digital archives of some of the most captivating shipwrecked women’s narratives that I worked to make available in the spring of 2018. In my selection of narratives that focus on the hardships endured by women while at sea, I wanted to make more visible the gendered and moralizing constraints placed on women while on land and how voyages at sea, while dangerous, often presented the promise of a more negotiable and open space for self-definition. More broadly, I wanted to make narratives that have often been overlooked or neglected more accessible to a larger audience.

Marian Moore’s narrative invites many ways to interpret Moore’s piece, from focusing on larger genre categorization (is this text truly a personal narrative as it presents itself to be, domestic fiction, a blend of genre?) to the provocative poetic disruptions which break Moore’s at times journalistic approach and at other times pathos-driven style of narration.

Julia Dean’s narrative, touted as a tale of a “veritable female Robinson Crusoe” depicts the wonderful adventures of a woman who remained on an uninhabited island for nine years. Positioning herself as a novice writer and most certainly not an egoist, Dean recounts her acts of bravery, most notably the depiction of her wrestling and bludgeoning an amphibious animal’s throat.

Since the Father of Mercies has seen it fit to deliver her from “the hands of barbarians,” Mrs. Eliza Fraser feels justified in publishing her own captivity narrative in spite of her reluctance and fear of her “indifferent education” and being deprived of her husband’s influence and support. Her self-described “plain, unvarnished tale” depicts her suffering experienced at the hands of what she disparagingly describes as “savages”, an unspecified group of Indigenous captors, which she finally evades with the help of a thirteen-man crew led by Lieutenant Otter and Graham. In the afterward, the reader is told that “probably through modesty” Mrs. Fraser has omitted the account of the birth of her baby which drowns while onboard the rescue vessel.

Flora A. Foster recounts her experiences of being wrecked en route to Peru off the coast of Patagonia with her husband, First Officer Robert Foster while aboard the MARY E. PACKER, a vessel built in Mystic, Connecticut. As fate would have it, after surviving their time on Carmen and finding passage back to New York aboard the brig EMILY T. SHELTON, Robert Foster plummets to his death from the topsail when only 300 miles from New York, making Foster’s descriptions early on in the narrative of how perilous the “cruel partings, the months and years of separation, the long dreary hours of loneliness and anxiety, the constant, unremitting strain of heart and brain” to only be understood by those separated from “dear ones at sea” all the more poignant.

Caroline Stoddard’s diary details her train trip from Boston, Massachusetts to San Francisco, California to join her husband Captain Thomas C. Stoddard for a voyage to Australia. Of particular note are Stoddard’s descriptions of her natural surroundings. Her style of writing can be likened to the “very pretty sheets of water, lying so quietly many hundred feet above the sea” that she uses to describe Donner Lake. This focus on the pleasantries of nature shifts from depictions of the Salt Lakes and the Sierra mountain range to a more critical tone of her physical environment after she experiences a harrowing shipwreck. Having to spend five days in a boat before being rescued by the brig COMMERCE of Sydney, Australia deeply unsettles Stoddard, but she continually returns to a focus on descriptions of nature to soothe her anxiety as she finds comfort in the “large bushes of heliotropes” in New Zealand that remind her of familiar “lilac bushes.”

Contained within William Dorset Fellowes text describing the tragic events of the Lady Hobart is the inclusion of the curious particulars of Emmanuel Sosa and his wife, Eleonora Garcia Sala, who were shipwrecked on the east coast of Africa. The hero identified in the narrative is Emmanuel, while his wife Eleonora is also described favorably but also complicatedly gendered as “a woman of a masculine courage.” Finding themselves in a compromising position with a group of Caffres, the heroic Emmanuel fails to listen both to the advice he received previously from a king about the threats he faces in the region and the admonitions of Eleonora that Sosa not trust the Caffres. Eleonora alone resists the attacks from the Caffres and is stripped of her clothing. Refusing to be seen in a vulnerable state, Eleonora buries herself in the sand while Sosa wanders aimlessly in search of resources to rescue his family to no avail.

In the longest text that I digitized this spring, William Allen’s Accounts of Shipwreck and of Other Disasters at Sea, is not only useful for mariners, but arguably for a larger public. What follows is what can be described as a compilation of melancholic and tragic greatest hits in the annals of shipwreck. Of particular interest are the sparse representations of women at sea, sometimes mentioned only by their first name with a reference to the vessel they were aboard, or cataloged simply by a number, such as the “317 women aboard who were lost at sea.” This particular text provides many narratives which can undoubtedly be mined for further historical and literary analysis.

Drew of the Sloop Nautilus and Others